The Long Walk

- Apr 11, 2018

- 4 min read

The trip took a bleak turn when Katie fell into a scathing diatribe about her people's mistreatment at the hands of white folk she calls the bilagáana.

“When men and women talk about Hwéeldi, they say it is something you cannot really talk about, or they say they would rather not talk about it….

They remember their relatives, families, and friends who were killed by the enemies. They watched them die, and they suffered with them, so they break into tears and start crying.

That is why we only know segments of stories, pieces here and there. Nobody really knows the whole story about Hwéeldi.”

— Old Navajo Quote

“They began by taking our possessions; then they took our land, then our livelihood, then our dignity. Now nothing is left of our beautiful culture but people whose entire identity is gone. And then, after any little bit of hope has been totally smothered, they take our lives away.”

“Katie, I didn’t…” René was at a loss too.

“At least your attackers went to trial. My attackers were never…”

“Honey…”

“Be quiet, Rory. Remember the cultural grief I was telling you about? Well, here it is, this is where it comes from, and I don’t see how it is ever, ever going to be made right.”

“Katie…”

“No, listen to me. Listen to what I’m telling you. You need to be quiet. You need to sit and listen.” Katie paused and composed herself. “In 1862 the ‘Indian Problem’ grew too big for the bilagáana to ignore. Now, a rumor was circulating throughout the greedy bilagáana world that gold was discovered in the Little Colorado River, the river running through the western part of Dinétah. Suddenly the Indian lands became too valuable to ignore; they had gold.

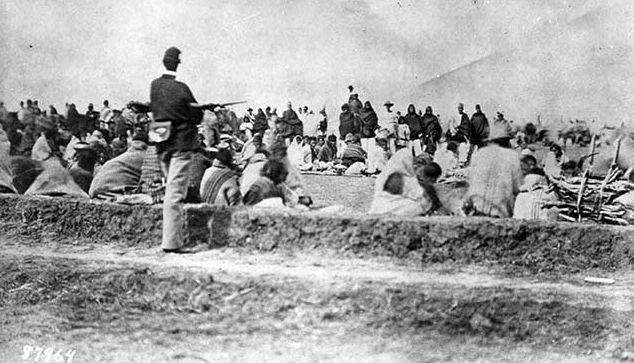

“The U.S. Army made war on the Mescalero Apache and Navajo Indian tribes, and your hero Kit Carson was the perfect man for the job. Given a commission in the army, men, horses, and weapons to invade Dinétah, he entered our land, killing anyone in his way. He destroyed our crops, our orchards, our hogans, and our livestock. Homeless, and without food many surrendered. Those who did not escaped into Canyon de Chelly. During a final standoff in January 1864, the remaining Diné surrendered. They were marched south to Fort Defiance and joined the other groups assembled there to begin the Long Walk.

“In its infinite wisdom, your government decided the Diné no longer belonged in Dinétah. A small piece of land along the Pecos River was found hundreds and hundreds of miles away, and it was expected to support eight thousand Navajos and Mescalero Apaches. Bilagáana called the place Fort Sumner. We called it Hwéeldi. It was three hundred miles east of Dinétah, and soldiers with horses and wagons herded the Diné into this hell.

Three hundred miles, they made all of us walk three hundred miles. Diné men, women, and children froze to death on the march from inadequate winter clothing, and many died of hunger from inadequate supplies. The dead were left where they lay to be picked apart and eaten by vultures, coyotes, and crows. Many people drowned crossing rivers. People were shot if they complained or stopped to help someone.

There is a story about a young mother who was going into labor. My relatives asked the Army to stop for a while and allow her to give birth. But the soldiers wouldn’t do it. They told the parents to leave their daughter behind. ‘Your daughter is not going to survive, anyway. Sooner or later she is going to die,’ they said…

“‘Go ahead,’ the daughter told them, ‘things might come out all right with me.’ Not long after they left, they heard a gunshot from where they’d left h

er. They never saw her again.

“We didn’t know where we were headed. When we finally reached Hwéeldi, the place was unfit to live on. The water was of poor quality, and there wasn’t enough of it. There was no wood for making fires. We were left there to die. We couldn’t even make hogans, so we dug holes in the ground for shelter.

“Finally, people in the east heard of our plight. They began campaigns to stop the genocide, and after three years at Hwéeldi, we were allowed to return to Dinétah. They gave us small amounts of food, and one or two sheep. The line of the Diné returning to Dinétah stretched for ten miles, imagine how many people it takes to form a ten-mile line.” Tears were coming down Katie’s face when she finished her story.

“Ellen, could you stop the car?” Rory asked.

She pulled off the highway.

Last Chapter Next Chapter

Guernica Blue Waters

***

***

***

Audiobook coming soon

***

***

The Long Walk: Butterfly Boy, Chapter 31